The euthanasia consultation is an emotionally charged situation that small animal practitioners deal with on a daily basis. Strategies that help reduce anxiety for the animal, its owners and the veterinary team are desirable. All parties wish for the end of life to be painless, peaceful and timely, but this places a heavy burden on the clinician to consistently achieve all of these goals. In the UK, there is considerable training on handling bereavement and client care during and after euthanasia, but there is less consideration toward adding sedation for the animal to the procedure routinely.

Current practice

The British Small Animal Veterinary Association (BSAVA) guidelines for euthanasia recommend injection of an overdose of a barbiturate solution, using pre-medicants for frightened or vicious animals (BSAVA, 2020a). Routine sedation with pre-medication drugs before euthanasia is advocated for by many clinicians, although the publications recommending this approach are mostly from the USA. The American Animal Hospital Association's euthanasia policy advises sedation first (Bishop et al, 2016). The Lap of Love group, cofounded by Drs Gardner and McVety in the USA (https://www.lapoflove.com), has produced a large body of work for the veterinary profession on how to competently manage euthanasia with extra compassion. They present sedation as a standard tool to ease the euthanasia process, comparing it to a veterinary anaesthetist preparing for general anaesthesia.

In the author's experience, sedation is not routinely administered in the UK. The fear of inducing hypotension, which could make venous access more difficult, is cited as the main reason for this reluctance. A further challenge to established practice is to also advocate administering the pentobarbital intravenously directly from a needle, if catheter placement is likely to be awkward or distressing for the owner. While the administration of anaesthetic agents through a preplaced intravenous catheter has become the norm in recent decades, placement of a catheter in front of an owner can be an onerous task. The veterinarian's anxiety is readily heightened by the emotionally charged atmosphere, but separating pet and owner in the final moments could be seen as showing great insensitivity. While blood sampling is confidently practised from a variety of peripheral veins, this is also a procedure regularly performed away from the scrutiny of an owner. Also, to suggest keeping the animal with their owner, sedating first and injecting directly off the needle using veins other than the cephalic is not likely to be regarded with great enthusiasm. The administration of pentobarbital via a preplaced intravenous catheter is efficient but this will not always solicit an ending that is low stress for the patient and optimal for the owner. Relaxing and reducing any pain for the animal before the injection of the euthanasia solution will extend the time taken and introduce some new variables, but in the author's experience this helps all parties feel the pet has peacefully gone to sleep rather than just ‘dropped dead’.

Sedative medication options

The fact that the safest and most predictable anaesthetic drug protocol is the one you are familiar with is usefully applicable here, as euthanasia is just another anaesthetic drug situation. Unless the animal has a pre-placed intravenous catheter, the sedative agent is usually given by the intramuscular route. Occasionally, for very cachetic or fractious animals, the subcutaneous route may be a better approach.

Ideally the medication will be characterised as small in volume, non-painful and with low viscosity. Currently there is no single agent that satisfies the quest for an anxiolytic, muscle relaxant and analgesic, with a gentle onset of action that results in profound sedation within a period of 5 to 10 minutes. Sedative combinations that can meet these requirements are commonly mixed in the same syringe, enabling a single primary injection. Generating a situation where the animal is perceived to be ‘fighting’ the medication is absolutely not desirable, so potent sedation is recommended along with a quiet atmosphere for a more efficacious impact.

The aim with sedation pre-euthanasia is to make the animal drowsy but still with accessible veins. Owners are often comforted to hear their beloved pet snoring and in an ideal scenario, we create the opportunity for the owner to cuddle their pet that may have been presented in great pain or with an avoidance to touch. It is worth noting that not all situations will call for profound sedation or any at all in some emergencies, for example in an animal with fulminant pulmonary oedema needing intravenous access and speedy action. However, the majority of euthanasia situations are not emergency scenarios and may have been planned well in advance of the event.

For dogs, the Lap of Love group recommends combinations of ketamine, xylazine or other alpha-agonists, acepromazine and butorphanol, and ketamine/opiate combinations for cats. Alpha-agonists have the major disadvantage of commonly inducing vomiting in cats, so these are best avoided. Outside the UK, for both cats and dogs, there is a popular combination product called Telazol/Zoletial that contains tiletamine (chemically related to ketamine) and a benzodiazepine. Ketamine can be painful when administered intramuscularly and is a controlled drug in the UK. While its controlled drug status does not rule it out as a useful component, the extra requirement to record the precise volume used on a named animal is an additional procedural pressure. Methadone also comes under the same controlled drug category, but as a very potent analgesic and sedative it could also be considered as the opiate of choice. When choosing medication in a non-recovery situation, topping up with more potent products is acceptable on a case-by-case basis. In gravely ill animals, excitement that reduces the efficacy of sedation is not much of a problem. There are differences to note between dogs and cats in choices mostly because cats, like very small dogs, have a low muscle mass to inject into. Drug choices and dose rates, as used by the author, are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Rates for pre-euthanasia sedation in dogs via the intramuscular route. Lower doses may be just as effective intravenously

| Drug (concentration) | Recommended dosing |

|---|---|

| Acepromazine (2 mg/ml) |

|

| Butorphanol (10 mg/ml) |

|

| Dexmedetomidine (0.5 mg/ml) |

|

| Additional options |

|

Table 2. Dose rates for cats for pre-euthanasia sedation

| Drug (concentration) | Recommended doses |

|---|---|

| Acepromazine (2 mg/ml) |

|

| Butorphanol (10 mg/ml) |

|

| Additional options |

|

Dogs

- Butorphanol has the advantage over buprenorphine of requiring lower volumes for comparable sedation. The established value of butorphanol as an anxiolytic for cardiac failure should also help practitioners feel more comfortable contemplating the use of this drug. Buprenorphine is a more potent analgesic than butorphanol but has a slower onset of action, while the other useful opiate alternative, methadone, is potent and rapid in onset. Butorphanol may actually be more effective than methadone when combined with dexmedetomidine for intravenous sedation in dogs (Trimble et al, 2018).

- Dexmedetomidine has analgesic effects at the premedication dose of 5 ug/kg. The higher sedation dose (10–15 ug/kg) could result in poor peripheral venous pressure so should be avoided unless an intravenous catheter is already in place and there is a small risk of inducing vomiting in the recently fed dog.

- Acepromazine is a very familiar product to clinicians, with good muscle relaxation, sedative and antiemetic properties, but poor anxiolysis. The sedation is unreliable when used alone and the animal may remain fully aware but unable to move much. It has hypotensive actions so high-end doses may be counterproductive. The BSAVA (2020b) formulary notes that the depth of sedation plateaus at 0.1mg/kg (0.5 ml per 10 kg using the 2mg/ml strength), so exceeding this will not be useful and is likely to exacerbate poor peripheral vein pressure.

- Benzodiazepines are widely used for their anxiolytic properties but diazepam is unreliably absorbed and painful when administered intramuscularly. Midazolam has good efficacy but is not available as a licenced product for us in animals. Benzodiazapines are most useful where intravenous access is already available.

Cats

- Butorphanol and acepromazine combinations work well in many cats. Butorphanol has better antiemetic effects in cats than buprenorphine (Bhalla et al, 2018).

- Dexmedetomidine or medetomidine use is associated with a high risk of vomiting and this can be distressing, so these should be avoided.

- Alfaxalone given intramuscularly can be a very effective sedative in cats (Tamura et al, 2015). It is licenced for sedation in Australia but not in the UK. It has a neutral pH so does not sting and an effective dose of 2.5 mg/kg has been established on healthy cats, so lower doses may be useful in very unwell cats and alongside other drugs.

- The author has administered highly diluted pentobarbital (1–2 parts saline) by the intraperitoneal route to cats, especially in frail or fractious individuals. Undiluted pentobarbital should not be injected into the abdomen without prior sedation as it is painful. Sedation onset is very dependent on the health of the cat and some very weak cats may succumb totally to this injection, often quickly. Should this happen, it can be reassuring to mention to the owner that it was a marker of the animal's tenuous grip on life. The reaction of the cat to the insertion of the needle and the injection is usually minimal and it is very easy to top up doses. The diluted solution passes easily through a 25G needle. In the anaesthetised cat, the final pentobarbital dose could alternatively be given by the intrarenal, intrahepatic or even the intracardiac route.

Dose rates of medication pre-euthanasia are dependent on both health status and anxiety levels. Very ill animals may become markedly sleepy with low doses, while aggressive animals can be barely affected. If sedation for euthanasia is unfamiliar for a veterinary team, then it can be helpful to start with animals that already have an established intravenous catheter line, using low doses to avoid very sudden onset sedation.

The reduction in tension within the room after the pet has been sedated is likely to be striking. When beginning euthanasia with intramuscular routes, choose long-legged, quiet, older animals and for extra assistance, select animals with good blood pressure (such as those with renal disease) to gain confidence. It is important to try to optimise the chances of achieving a good outcome, especially when a new protocol is trialled, as choosing an aggressive, short-limbed dog for a novel approach is not likely to win over a dubious clinical team. Sedation protocols are well described in the BSAVA formulary (2020b).

Adminstration of the sedative

Stating the value of attaining relaxation and pain relief in a time frame of approximately 10 to 15 minutes should always precede the first injection, as it is reassuring for owners know what to expect. When administered via the intravenous route, sedation may be so rapid in onset that the desired gentle slide does not happen, so clinicians should start with low doses intravenously when familiarising themselves with intravenous sedation. With a line in place, a top up dose is very easy to administer. The lumbar muscles are the preferred site for intramuscular injections although any accessible muscle group can be used as this is a non-recovery procedure. A fine gauge needle should be opted for (25G for cats and 23G dogs). Try and slide the injection in rather than stab, as the owner may notice and overinterpret the sudden movement. There is no need to draw back and check for blood with intramuscular injections in a euthanasia situation. Another veterinary team member should gently hold the head to avoid unexpected movement and the author usually informs the owner before the injection that their pet may show a small surprise reaction on injection. Offering tasty food to divert the animal can also be very helpful. If an intravenous catheter is already in place, connecting it up to a fluid bag can enable administration via the inline port. If veterinary staff can be further from the head this allows the family to be closer to their pet (Figure 1). The author would still strongly recommend sedation in patients with intravenous catheters, as the intensity of the experience for animal and owner is reduced.

Owners often appreciate the privacy of having 10 minutes with their animal with no veterinary personnel in the room, after the sedative has been given. The author always reminds owners that they can ask for support at any time, although it is still prudent to discreetly check on the situation periodically. There are two benefits to the veterinary team leaving the room. First, most animals relax faster, which is useful as sedative efficacy is greater in calmer animals, and second, the owners are less self conscious about being upset.

Providing chocolate, biscuits, cake or cat food for dogs to eat works remarkably well before and during the sedative injection, as well as for a little while after in some cases, by helping to distract the animal and even amuse owners at a time of sadness. Cats rarely eat but if they are likely to, some tasty sachet food can be fed from the fingertips (as providing a full bowl can look depressing if they have no interest). The mood lift associated with eating food at the consultation is another reason why the author uses very low doses of dexmedetomidine, as vomiting is not desirable. Should this happen, a useful tip from Drs Gardner and McVety from the Lap of Love is to point out that it was nice that they had been well enough to have had a good meal so close to the end.

Venous access for pentobarbital

With a well sedated pet, the pentobarbital administration options are expanded, as restraint and minimising anxiety are no longer issues. For clinicians who are uncomfortable with placing an intravenous catheter while being watched, this is the point where owners can be quietly suggested to look aside or even step out for a moment while the team places a line. Use of clippers should be avoided during euthanasia if possible as the sound is intrusive, may rouse the patient and sterility is not important. Cutting the fur with the convex arc of curved scissors, lightly touching the skin during cutting, is often more effective than progressive shortening with only the tip. Ensure sufficient fur has been trimmed so that the vein is easy to visualise.

There are many papers describing the range of veins that can be used for intravenous access. It is important to remember that lateral ear veins are very useful in dogs such as Basset Hounds and the medial branch of the cephalic vein can be accessed on the downside limb readily in a recumbent animal (Figure 2). Clinicians are not restricted to the venous route as intra renal, intrahepatic and intracardiac are all described but all of these should only be used in the unconscious animal according to the American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines (Bishop et al, 2016; Gardner, 2018). The ease of intraperitoneal pentobarbital administration in cats is worthy of note, it can also be very effective in dogs. As a standalone route, the dose is three to four times greater than the intravenous doses and can take 45–60 minutes to take effect (Gardner, 2018), although in cats the author has usually found that 1–15 minutes is the usual range. The author has even achieved a gentle ending by injecting a large splenic tumour in an obese dog with short, twisted legs and small ears after butorphanol, dexmedetomidine and acepromazine sedation with the owner present. A tip from the Lap of Love team is to only specify which technique you will use after the sedative effect has been evaluated. It is important to remind owners that as every pet is unique, vets want to choose the best one for each individual according to how they respond (Gardner, 2018). Changes of plan can generate feelings of upset and lack of control. Should it be necessary to give extra sedation, this should be handled as an absolutely normal event and not a mistake.

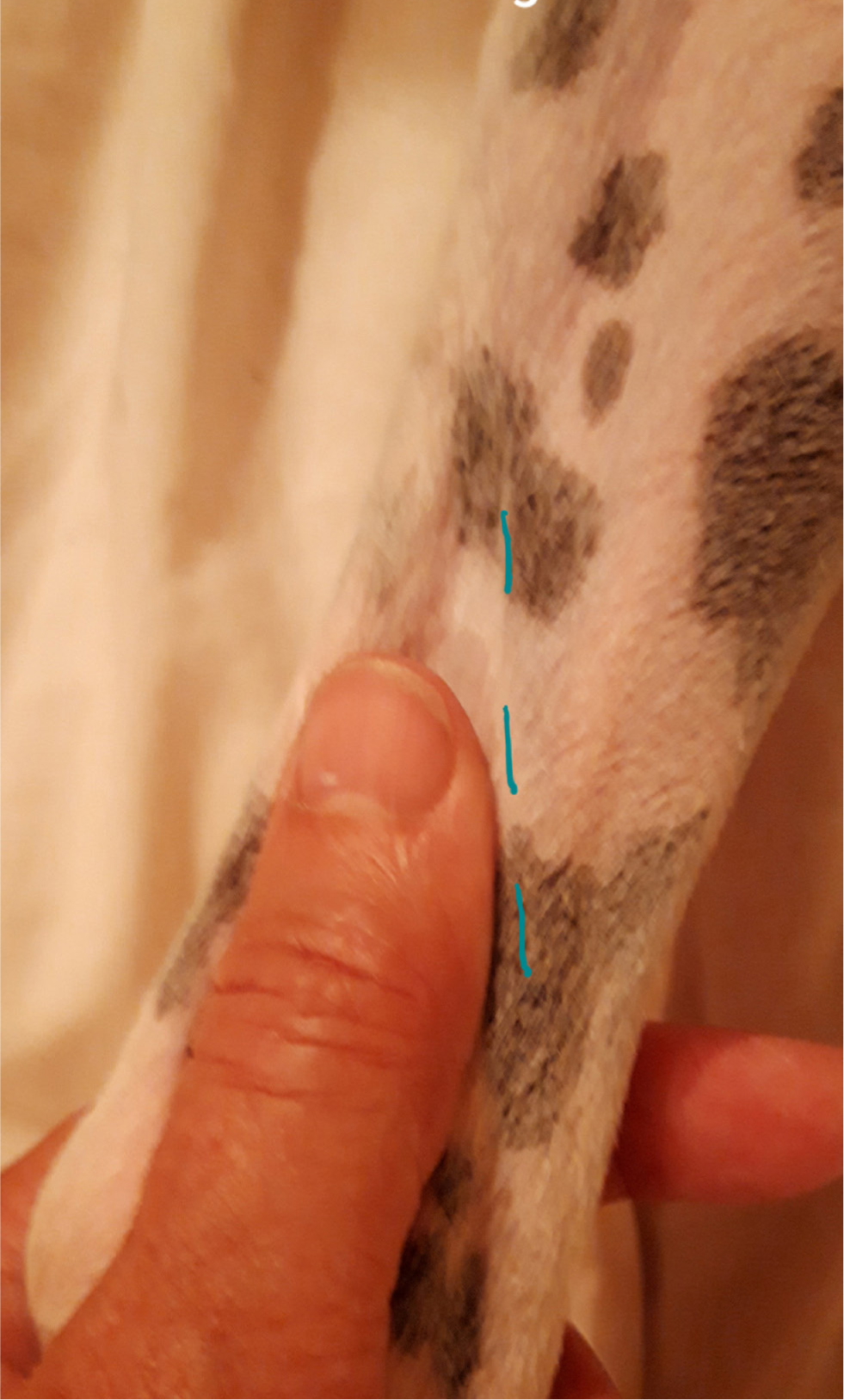

The author prefers to use the lateral saphenous vein in dogs (Figure 3), as the good distance from the head allows owners to focus on their pet's face without obstruction. This is quite mobile in contrast to the cephalic vein, so gently stabilising the vein by tightening the skin slightly using your free thumb is useful (Figures 3 and 4). Contrastingly to the cephalic vein, a little darting action can make entering the vein a little easier. The mobility means it is often simpler to use a needle than place an intravenous catheter in this vein. The only disadvantage of using a 25G needle in a large dog is that it takes more time and strength to infuse pentobarbital but, if the animal is already very relaxed, this is inconsequential.

The pentobarbital data sheet dose of 0.4 ml/kg (80 mg/kg) for 200 mg/ml for products in the UK is effective, especially in very ill or well sedated patients, so there is no need to fill the syringe with extra ‘just to be safe’.

It is essential that the family knows when the pet has died, even though it is easy to forget to state what is obvious to those who are experienced. Auscultating the heart twice and checking the pupil size is a useful habit because owners should be left in no doubt that death has occurred, as the ‘just looks asleep’ view can haunt them if we omit declaring death.

Conclusions

Sedating pre-euthanasia makes a profound impact on the quality of euthanasia. The end of life becomes a slower and a less emotionally taxing process for everyone involved. When intravenous catheter placement is not a simple option, sedation may actually ease intravenous pentobarbital access. Sedatives must be chosen with care with consideration given to potency, low volume and freedom from pain. The discreet administration of all medications at this sensitive time will also improve the experience.

KEY POINTS

- A relaxed and pain-free pet can markedly improve the experience for everyone who cares for the animal.

- Allow at least an extra 15 minutes to the euthanasia consultation when sedating.

- Do not commit to your final route of pentobarbital until you have evaluated the response to sedation, to avoid the angst of everyone feeling that something has gone wrong.

- Sedatives work better if veterinary personnel leave the room shortly after administration.

FURTHER READING

- The Lap of Love website is an excellent resource for practical and sensitive advice on euthanasia management (https://www.lapoflove.com)

- The paper from the co-founders Drs Gardner and McVety ‘Handling Euthanasia in Your Practice’ is a useful resource (https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/05/TVP_2016-0102_PB_Euthanasia.pdf)